If We Had Known: Rethinking First‑Time Gynecological and Sexual Experiences Through the Lens of Hymenectomy

By Alicea Peyton, PhD

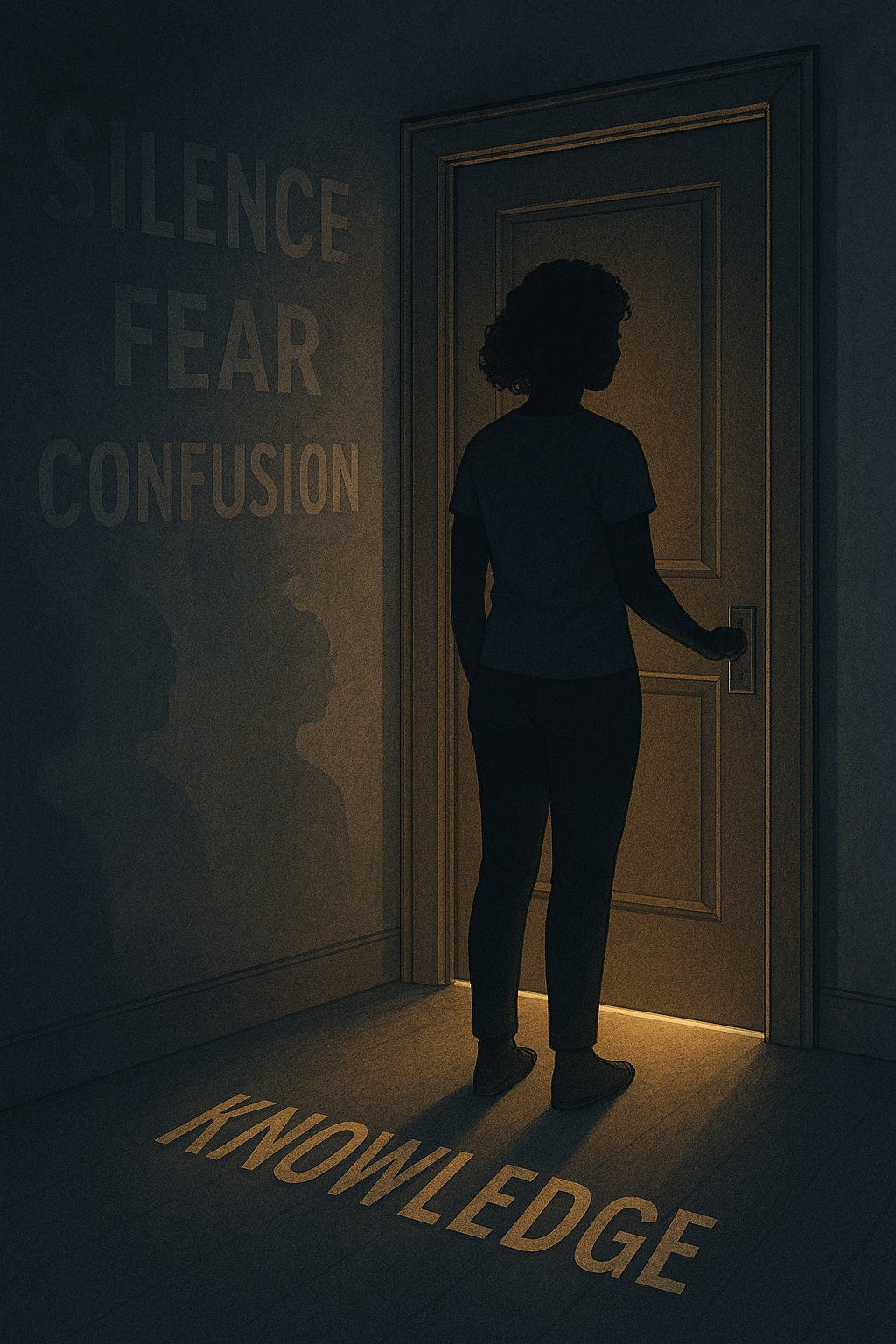

A lot of us look back on our first gynecological exam or sexual experience and remember a mix of confusion, fear, and just trying to get through it. Most people assumed the discomfort was normal, or that their bodies just weren’t “ready,” or that something about them was off. Those early moments weren’t shaped only by anatomy—they were shaped by silence. Silence in our families. Silence in school. Silence in doctor’s offices. Silence in the cultural stories we grew up with about the hymen. Nobody explained that hymenal variations exist. Nobody said they could affect penetration. And almost nobody mentioned that a simple, low‑risk procedure like hymenectomy was even an option. So many of us internalized the idea that pain was expected, fear was standard, and if something hurt, it was our fault for not “relaxing” enough.

Thinking about how different those first experiences might have been if we had real information opens up a much bigger conversation about autonomy, consent, and the emotional weight people carry into their first encounters with gynecologic care or sexual intimacy. For some, knowing about hymenectomy could have reframed pain as something treatable instead of something to endure. For others, it might have eased years of anxiety—the dread before a first pelvic exam, the hesitation with tampons, the fear around first‑time sex. And for many, it could have offered a sense of agency: the understanding that if something felt wrong, there were options besides pushing through or blaming yourself.

This isn’t about promoting surgery. It’s about naming the ways limited education, cultural myths, and medical gatekeeping shape how people understand their bodies. The hymen has carried centuries of symbolism—purity, morality, identity—yet almost no practical information. Many people grow up believing the hymen “breaks,” that penetration is supposed to hurt, or that pain is some kind of rite of passage. These ideas aren’t just inaccurate; they can be harmful. They shape expectations, influence consent, and create a foundation of fear that follows people well into adulthood.

When we imagine how things could have been with accurate information, we also start to see how things could change moving forward. A young person who knows hymenal variations exist might walk into their first pelvic exam with less fear. Someone who understands that pain isn’t inevitable might feel more confident advocating for themselves. A person who knows hymenectomy is an option might seek care earlier instead of avoiding it for years. And someone dealing with fear‑based responses, sensory sensitivities, or trauma‑related avoidance might finally feel seen instead of dismissed.

There’s also a mental health layer that rarely gets talked about. Fear of penetration, sensory overload, trauma histories, and conditioned avoidance aren’t “in your head.” They’re real, embodied experiences that deserve compassionate, interdisciplinary care. When people aren’t given accurate information, they often interpret their distress as a personal flaw instead of a legitimate response shaped by biology, psychology, social context, and meaning‑making. Knowledge doesn’t erase distress, but it can change how people understand it—and how they seek support.

Asking how our first experiences might have been different isn’t about regret. It’s about imagining a more informed, more compassionate future. It challenges the silence that shaped so many people’s early encounters with gynecologic care and sexual intimacy. And it opens space for new conversations—about autonomy, education, interdisciplinary care, and the right to understand one’s own body without shame or fear.

So, the question stands, not as judgment but as an invitation: How might your first experience have been different if you had known hymenectomy was an option?

If you would like to read the literature review supporting this conversation, click the following link: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.22408.28163